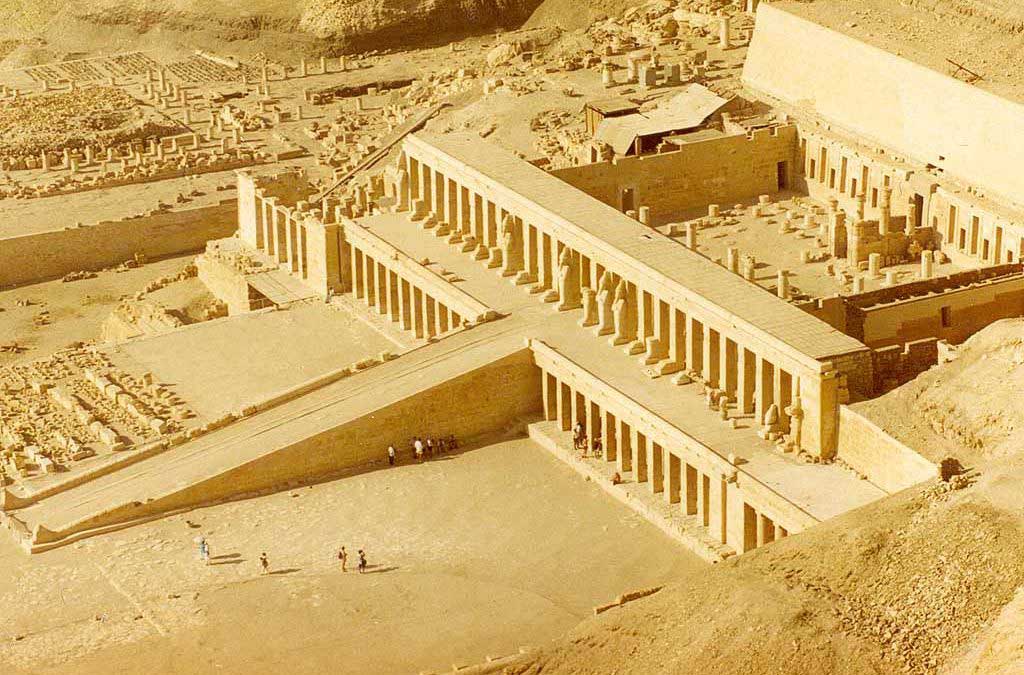

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, also known as the Djeser-Djeseru (Holy of Holies), is a mortuary temple of Ancient Egypt located in Upper Egypt. Built for the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut, who died in 1458 BC, the temple is located beneath the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari on the west bank of the Nile near the Valley of the Kings. This mortuary temple is dedicated to Amun and Hatshepsut and is situated next to the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, which served both as an inspiration and, later, a quarry. It is considered one of the incomparable monuments of ancient Egypt.

This article contains information about Hatchepsut Temple including:

Who is Queen Hatchepsut?

Hatshepsut was a female pharaoh who had herself represented pictorially as a male. She served as co-regent with her nephew Thutmose III (c.1479-1425 B.C.E.).

Hatshepsut is distinguished in history for being one of the most successful pharaohs of Ancient Egypt. She was also a woman and is generally regarded as one of the first female historical figures whose exploits are known to modern historians. Hatshepsut was the fifth pharaoh of the 18th dynasty during the New Kingdom. The dates of her reign are debated by historians, but she is thought to have ruled Egypt for 22 years from 1470 to 1458 BC. Hatshepsut is distinguished in history for being one of the most successful pharaohs of Ancient Egypt.

Hatshepsut was the Egyptian King Thutmose I and his wife queen Ahmose only child, she was one of the greatest queens and the second who ruled ancient Egypt. Hatshepsut was the fifth pharaoh of the eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt. She was the second confirmed female pharaoh who ruled Egypt, the first one was sobekneferu. Hatsheosut take over the rule of Egypt in 1478 BC.

Where is Hatchepsut Temple located?

Hatshepsut (c.1473–1458 BC), the queen who became Pharaoh, built a magnificent temple at Deir al-Bahari, on the west back of Luxor. It lies directly across the Nile from Karnak Temple, the main sanctuary of the god Amun. Hatshepsut’s temple, Djeser-djeseru “the Holy of Holies” was designed by the chief steward of Amun, Senenmut.

Queen Hatshepsut temple is located in Upper Egypt beneath the cliffs of “Deir El-Bahari“, a name that derives from the former monastery built during the Coptic era, about 17 miles northwest of Luxor on the west bank of the river in western Thebes, the great capital of Egypt during Egypt New Kingdom (1550- 1050 BC). It is sited next to the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II and marks the entrance of the Valley of the Kings that you can visit during your luxury Egypt tours.

The temple consists of three levels each of which has a colonnade at its far end. On the uppermost level, an open courtyard lies just beyond the portico. Mummiform statues of Hatshepsut as Osiris, the god of the dead, lean against its pillars.

Hatshepsut, an admirer of Mentuhotep II’s temple had her own designed to mirror it but on a much grander scale and, just in case anyone should miss the comparison, ordered it built right next to the older temple. On the south side of Hatshepsut’s temple lie the remains of the Temple of Montuhotep, built for the founder of the 11th dynasty and one of the oldest temples thus far discovered in Thebes, and the Temple of Tuthmosis III, Hatshepsut’s successor. Both are in ruins. Hatshepsut was always keenly aware of ways in which to elevate her public image and immortalize her name; the mortuary temple achieved both ends.

How long did Queen Hatchepsut ruled Egypt?

She became Egypt queen when she married her half-brother, Thutmose II when she was 12. Being a Pharaoh, Hatshepsut expanded Egyptian trade and establish promising building projects, most famous one was the temple of Deir el-Bahri. Her reign was the longest female pharaoh reigning, ruing Egypt for more than 20 years in the 15th century. beginning in 1478 BC, she served as a queen alongside her husband.

During her reign Hatshepsut was successful in re-establishing trade relationships that had been disrupted by a foreign occupation of Egypt by the Hyksos people. It is this success in economic matters that led to her being regarded as such a successful ruler.

She also Built a sea voyage to punt land, a place located on the northeast coast of Africa, where they used to trade with inhabitants bringing back “marvels”. The most famous of these trading relationships was with the land of Punt (placed by historians in central Africa), an accomplishment immortalized in the reliefs of her mortuary temple on the West Bank of the Nile at Luxor (ancient Thebes). As a result of Hatshepsut’s efforts, Egypt enjoyed a period of economic prosperity during and immediately following her rule.

Her era was peaceful and she ordered to build the great temple of Deir el-Bahari at Luxor, Hatshepsut was also a prolific builder. The number of building projects undertaken and the elevation of architectural style during her rule is evidence of the economic prosperity that Egypt enjoyed during her reign, as well as her desire to immortalize her influence as the ruler of Egypt.

She built hundreds of buildings throughout the Nile Valley and there was a huge amount of statuary produced with her likeness. By far the most famous building attributed to Hatshepsut is her mortuary temple, known as Deir Al-Bahiri or Hatshepsut Temple. The unique collonaded design of this temple is still admired by art historians as unrivaled until the rise of Classical Greece.

The design and the Layout of Hatchepsut Temple

At Deir Al Bahri, the eyes first focus on the dramatic rugged limestone cliffs that rise nearly 300m above the desert plain, only to realise that at the foot of all this immense beauty lies a monument even more extraordinary, the dazzling Temple of Hatshepsut. The almost-modern-looking temple blends in beautifully with the cliffs from which it is partly cut – a marriage made in heaven. Most of what you see has been painstakingly reconstructed.

It was designed by Senenmut, a courtier at Hatshepsut’s court and perhaps also her lover. If the design seems unusual, note that it did in fact feature all the things a memorial temple usually had, including the rising central axis and a three-part plan, but it had to be adapted to the chosen site: almost exactly on the same line as the Temple of Amun at Karnak, and near an older shrine to the goddess Hathor.

The temple was vandalised over the centuries: Tuthmosis III removed his stepmother’s name whenever he could; Akhenaten removed all references to Amun; and the early Christians turned it into a monastery.

A large ramp leads to the two upper terraces. The best-preserved reliefs are on the middle terrace. The reliefs on the north colonnade record Hatshepsut’s divine birth and at the end of it is the Chapel of Anubis, with well-preserved colourful reliefs of a disfigured Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III in the presence of Anubis, Ra-Horakhty and Hathor. The wonderfully detailed reliefs in the Punt Colonnade to the left of the entrance tell the story of the expedition to the Land of Punt to collect myrrh trees needed for the incense used in temple ceremonies. There are depictions of the strange animals and exotic plants seen there, the foreign architecture and landscapes as well as the different-looking people. At the end of this colonnade is the Hathor Chapel, with two chambers both with Hathor-headed columns. Reliefs on the west wall show, if you have a torch, Hathor as a cow licking Hatshepsut’s hand, and the queen drinking from Hathor’s udder. On the north wall is a faded relief of Hatshepsut’s soldiers in naval dress in the goddess’ honour. Beyond the pillared halls is a three-roomed chapel cut into the rock, now closed to the public, with reliefs of the queen in front of the deities and, behind the door, a small figure of Senenmut, the temple’s architect and, some believe, Hatshepsut’s lover.

The upper terrace, restored by a Polish-Egyptian team over the last 25 years, had 24 colossal Osiris statues, some of which are left. The central pink-granite doorway leads into the Sanctuary of Amun, which is hewn out of the cliff.

On the south side of Hatshepsut’s temple lie the remains of the Temple of Montuhotep, built for the founder of the 11th dynasty and one of the oldest temples thus far discovered in Thebes, and the Temple of Tuthmosis III, Hatshepsut’s successor. Both are in ruins.

The osiride statues at the temple of Hatchepsut

This Osiride statue stands in front of one of the columns on the third level of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. Osiris was the Egyptian god of fertility, resurrection, and the next world. He was usually pictured wrapped as a mummy, holding a crook and flail as scepters and as symbols of his control over nature. Combined with the crook (on the right) is a was scepter (hieroglyphic sign meaning “dominion”). Combined with the flail (on the left) is an ankh (hieroglyphic sign meaning “life”). This statue of Osiris has the delicate features of Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh. He wears the Double Crown of Egypt and a false beard with a curved tip (indicative of divinity).

Hathor Chapel at the Temple of Hatchepsut

Since Hathor was the guardian of the Deir el-Bahri area, it is appropriate to find a chapel dedicated to her within Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple (south end of second level). The columns which fill the court of this chapel have Hathor columns, each of which resemble a sistrum, a percussion instrument associated with the goddess of love and music. The capital is a female head with cow ears topped with a crown, the curved sides ending in spirals, perhaps suggestive of cow horns. The central section of the crown is a shrine in which two uraei (rearing cobras with spread hoods) are surmounted by sun disks. A cavetto cornice tops the whole.

Anubis Chapel at the temple of Hatchepsut

At the north end of the second level of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple, is the Anubis Chapel. Anubis was the god of embalming and the cemetery. He was frequently represented with the body of a man and the head of a jackal, as he is shown here. Anubis sits on a throne, which, in turn, rests on a small plinth. He faces a pile of offerings which reaches in eight levels from the bottom to the top of the register.

Although much of the color is now gone, one can imagine the vibrancy of the original painting. The Egyptians used mineral pigments; so the colors have not faded as much as vegetable pigments would have

Third Level of Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple

Among the loose blocks on the third level of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple is this one decorated with a raised relief carving of Horus as a falcon. He wears the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, reminding us that the pharaoh was the earthly manifestation of the god, who was ruler of the heavens.